Part A

Sediment & Sedimentary Structures

The process of making sedimentary rocks starts with the weathering of rocks at the Earth's surface. Weathering can either be mechanical (physically breaking rocks into smaller pieces) or chemical (changing the composition of a rock by chemical processes). Weathered rock can then be eroded (moved by wind, water, or ice) and deposited (settling of material) as loose solid debris or sediment. Sedimentary structures are commonly preserved in sediment (e.g., ripple marks, mud cracks, etc.). A few simple observations of sediment and sedimentary structures can yield important information about the environment in which they were deposited. Because we can observe how sediment and sedimentary structures form today, we can thus interpret how they formed in the geologic past.

|

Figure 5-2. Beach sediment of the Big Island of Hawaii. Sand made up of carbonate rock (bleached coral), basalt, and shell fragments (left). A carbonate-dominated gravel beach (right). |

|

Clastic Sediment

Let's first look at clastic sedimentary rocks: ones made of sediment or broken pieces (clasts or fragments) of other rocks or shells (see Figures 5-3 through 5-5). Clasts can range in size (fine to coarse), shape (rounded to angular), and sorting (poor to well).

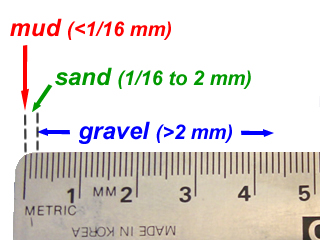

Clast Size

> Sediment particle (clast or grain) sizes include gravel-sized (>2 mm), sand-sized (2 mm to 1/16 mm), and mud-sized (<1/16 mm). Each of these size categories can be subdivided into even smaller units (e.g., silt = 1/16 mm to 1/256 mm, clay = <1/256 mm, etc.).

> Clast size is related to the distance sediment traveled prior to deposition. Typically, the farther the sediment has traveled, the smaller the clast size due to abrasion.

> Clast size can also be related to current energy, with movement of larger clasts requiring stronger current. Conversely, smaller clasts require lower energy environments for them to settle out of suspension.

|

|

|

Figure 5-3. Clast sizes: gravel (>2 mm), sand (1/16 mm to 2 mm), and mud (<1/16 mm). |

|

Example 1 |

|

|

|

What is the size of most of the clasts in the image above? |

|

Gravel (>2 mm) Remember, 0.5 m = 50 cm = 500 mm. |

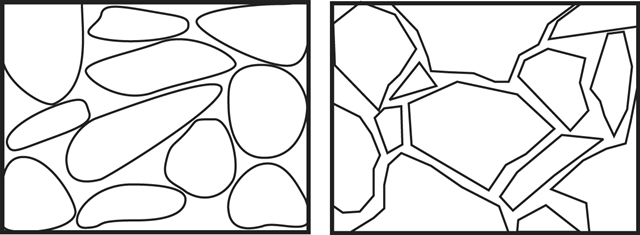

Clast Rounding

> Rounding of sediment refers to the relative smoothness of particle corners (rounded to angular).

> Rounding can be related to distance of transportation or the amount of current energy. For example, well-rounded sediment reflects long transportation distances or high-energy currents (like wave action along a beach) because of greater abrasion.

|

|

|

Figure 5-4. Clast rounding: well rounded (left) and angular (right). |

|

Example 2 |

|

|

|

Are the clasts in the image above rounded or angular? |

|

Rounded |

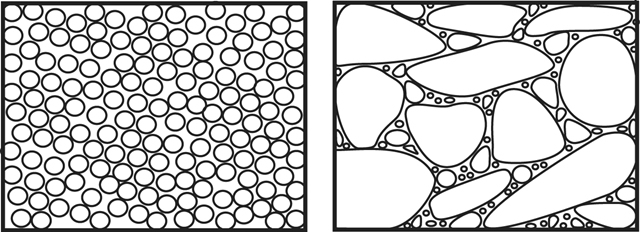

Clast Sorting

> Sorting refers to the range of clast sizes in sediment.

> Well-sorted sediment has equal-sized pieces, whereas poorly-sorted sediment has both large and small pieces.

> Sorting is related to the distance sediment traveled prior to deposition. With increasing distance, sediment becomes more well sorted as larger particles drop out.

> Sorting is also related to the type of current transportation, with wind- and water-carried sediment (sand and mud) more likely to be well sorted than sediment carried by ice.

|

|

|

Figure 5-5. Clast sorting: well-sorted sediment where most of the clasts are similar in size (left) and poorly-sorted sediment, where there is a range of clast sizes (right). |

|

Example 3 |

|

|

|

Describe the sorting of the clasts in the image above. |

|

Poorly sorted |

Because sedimentary rocks were once sediment, they record the surface conditions of the past, such as where they originated, how far they were transported, when and where they were deposited, etc. Thus, studying sediment is very important in the understanding the sedimentary rocks they become.

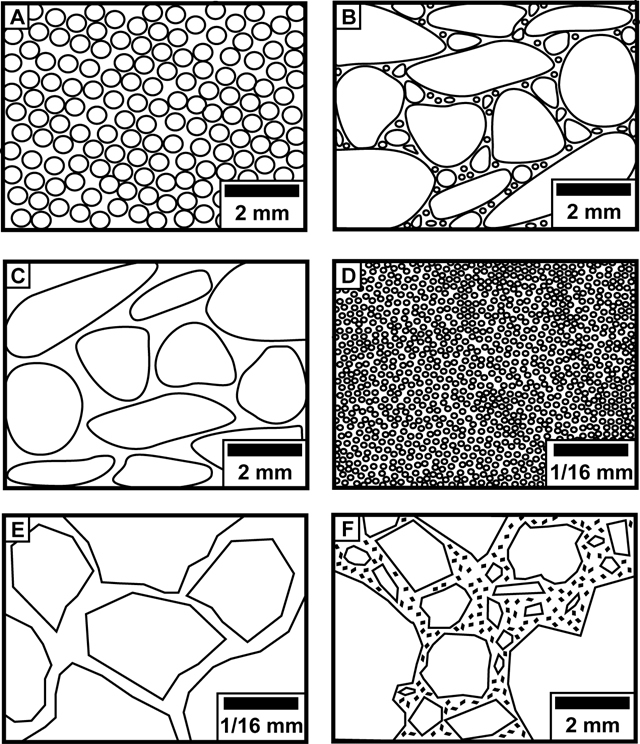

Reference the previous discussion and the sediment panels shown in Figure 5-6 for questions A01 through A10. Pay attention to the scale!

|

|

|

Figure 5-6. Panels representing sediments having differing size, rounding, and sorting. |

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

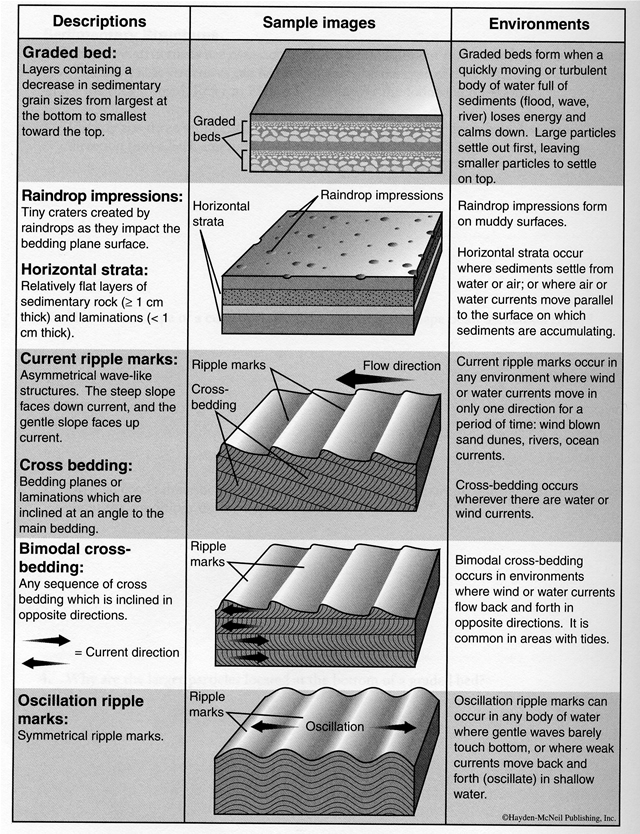

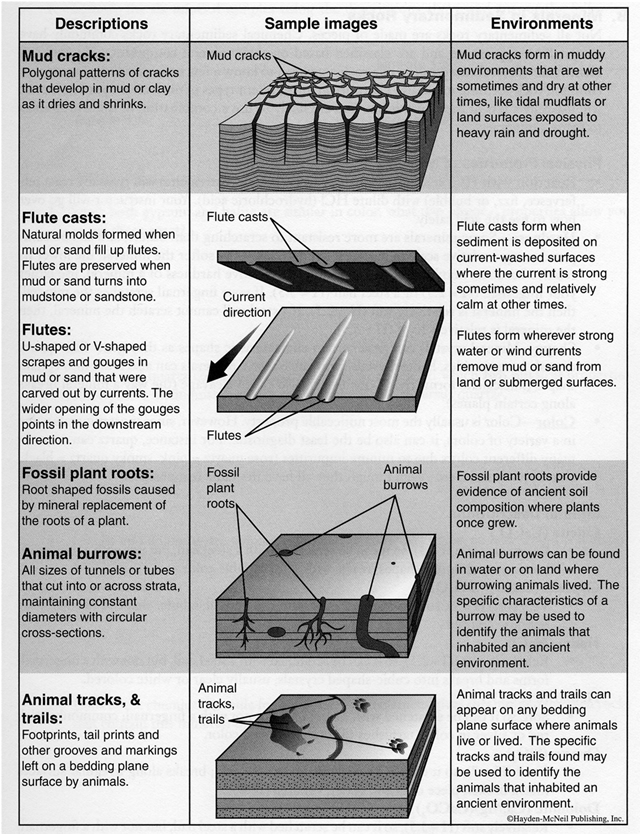

Sedimentary Structures

Sedimentary structures are formed before lithification and are commonly preserved in sediment (for example, ripple marks or mud cracks). Because we can observe how sedimentary structures form today, we can interpret how they formed in sediments in the geologic past. Not only that, but these structures can be used to describe the type of depositional environment in which the sediment was deposited and the rock ultimately formed. See Figures 5-7 and 5-8 for examples and descriptions of various sedimentary structures.

|

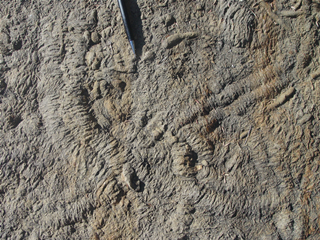

Figure 5-7. Common sedimentary structures. Clockwise from top left: symmetrical ripple marks, asymmetrical ripple marks, mud cracks (or dessication cracks), crawling trace fossils (trails), a foot print trace fossil (track), and cross bedding. |

|

|

Figure 5-8. Charts of common sedimentary structures that form in soft sediment and are found in sedimentary rock (courtesy Hayden-McNeil Publishing). |

|

|

Example 4 |

|

|

|

Name this type of sedimentary structure. |

|

Cross bedding |

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()