Part A

Metamorphism & Metamorphic Rocks

Metamorphism can create new rocks form from pre-existing rocks based on the pressure, temperature, and the fluid activity in the rock. Metamorphic rocks are formed from some original rock type (igneous, metamorphic, or sedimentary) and are referred to as the parent rock (protolith). For instance, if a limestone (protolith) is buried and exposed to high temperatures, it will form a new rock called marble (metamorphic rock). Depending on the degree or intensity of metamorphism (metamorphic grade), various elements will be rearranged and new minerals will form. The composition of the original rock and the intensity of the metamorphism determine how much the rock will change. Sometimes new minerals can grow in the (like garnet or kyanite) or even new layering can form. Increasing temperature will progressively recrystallize the minerals in rocks, and makes them harder and denser than the original rock, but all changes during metamorphism occur while the rock is solid.

|

Figure 7-2. Paleoproterozoic metamorphic rocks of the Grand Canyon. The dark-colored Brahma Schist forms much of the Inner Gorge to the west of Plateau Point (left). Gneissic rocks along Bright Angel Creek (right). |

|

Types of Metamorphism

There are different types of metamorphic environments depending on the METAMORPHIC GRADE. The general types of metamorphism include:

Diagenesis

> Very low temperature and pressure.

> Occurs after sedimentary burial and before or during lithification (a.k.a. burial metamorphism).

Regional metamorphism

> Low to high pressures and temperatures.

> Directed pressure causes the platy minerals to RE-ALIGN in a more parallel orientation, forming a layered or foliated metamorphic rock texture.

> Widespread metamorphic effects are associated with tectonically active areas, especially subduction zones.

Contact metamorphism

> High temperatures and low pressures.

> Since directed pressure is not a major factor in this type of metamorphism, resulting metamorphic rock types have randomly oriented crystals and thus have textures that are massive or non-foliated.

> High-temperature mineral RECRYSTALLIZATION occurs.

> Occurs locally near igneous intrusions. The metamorphic zone around an intrusion is referred to as a "CONTACT AUREOLE" or a "bake zone". The size of the aureole depend on the volume of the heat-generating intrusion, but the effects are typically more localized than regional metamorphism.

> Magma-driven hydrothermal fluid activity is commonly associated with this type of metamorphism (contact metamorphism is typically gradational with hydrothermal metamorphism).

Blueschist metamorphism

> High pressures and low temperatures.

> Eventually grades into greenschist metamorphism (a type of regional metamorphism) as temperatures rise.

> Occurs during rapid tectonic burial at subduction zones.

Dynamic metamorphism

> Localized high pressures and temperatures related to fault zones and shear zones.

> Brittle deformation (crushing, grinding) includes cataclastic metamorphism that produces fault gouge and fault breccia.

> Ductile deformation (flow) occurs deeper within the crust and produces finely layered rocks called mylonites.

Impact metamorphism

> Related to the localized, but very high pressures associated with meteorite/comet impacts.

> Rocks can be shattered and contain high-pressure minerals (stishovite, coesite, etc.).

Metamorphic Rock Textures

At the introductory level, metamorphic rocks are probably the easiest to recognize and identify. This is because there are only two major textural types and the rocks are fairly distinctive. In reality, metamorphic rocks can be some of the most challenging to identify and interpret. We'll keep it simple for now. There are two basic types of metamorphic rock texture, foliated and non-foliated (see Figure 7-3).

|

Figure 7-3. Foliated and nonfoliated metamorphic rocks and textures. Foliated migmatite gneiss in Gneiss Canyon of the western Grand Canyon (left). |

|

Foliated metamorphic textures

> In layered or foliated metamorphic rocks, the platy minerals are aligned in a parallel orientation.

> The size of the minerals (very fine-grained, fine grained, coarse grained) is related to the intensity of metamorphism, with the larger crystal sizes representing higher intensities of metamorphism.

> The specific type of foliation (slaty cleavage, schistosity, gneissic banding) can also be related to the intensity of metamorphism.

> Foliated rocks are primarily distinguished by their specific type of foliation.

> Foliated textures are generally associated with types of metamorphism involving directed pressure, like regional, blueschist, or dynamic.

IMPORTANT NOTE - Some rocks lacking abundant amounts of platy minerals will not form a well-developed foliation, even if they are subjected to intense pressure.

Nonfoliated metamorphic textures

> In massive or non-foliated metamorphic rocks, there is no preferred orientation of grains or crystals.

> Clast boundaries are recrystallized, making the rock more resistant.

> The degree of recrystallization may be related to the magnitude thermal effect from the intrusion.

> Non-foliated rocks are primarily identified by their composition (mineral content). For example, test to see if the rock reacts with HCl (it will fizz if made of calcite), or scratch the rock to check its hardness (quartz is hard, H=7; calcite is soft, H=3).

> Because they lack layering, nonfoliated textures are typically associated with contact metamorphism.

Common Metamorphic Rocks

Foliated Rocks

> A foliated, very fine-grained metamorphic rock.

> The platy minerals (micas) are too small to be seen without the aid of a microscope.

> Breaks easily along well defined, parallel flat surfaces.

> Color is highly variable (black, greenish gray, purple, red, etc.).

> Metamorphic grade - Low / low temperatures and high directed pressures (regional metamorphism).

> Protoliths - Derived from mudstone.

> Arizona examples - Breadpan Formation (central Arizona); Texas Gulch Formation (central Arizona).

> A foliated, fine-grained metamorphic rock.

> Can be distinguished from slate by phyllite's slightly shinier, satin-like sheen (platy minerals reflecting light), and the presence of wrinkles (crenulations) on the flat surfaces.

> Metamorphic grade - Low-moderate / moderate-high temperatures and directed pressures (regional metamorphism).

> Protoliths - Derived primarily from mudstone.

> Arizona examples - Various Proterozoic phyllite units in southern and central Arizona (e.g., the Phoenix Mountains, the Cave Creek area north of Phoenix, etc.).

> A foliated, coarsely crystalline metamorphic rock.

> Schist is composed of minerals large enough to see with the unaided eye.

> Platy minerals (like muscovite and biotite) commonly predominate, which may give schist an almost "fish scale" appearance.

> Breaks along irregular, sub-planar surfaces.

> Metamorphic grade - Moderate-high / moderate to high temperatures and directed pressures (regional metamorphism).

> Protoliths - Derived from a several possible protoliths (like mudstone or assorted volcanics).

>> If derived from mudstone, the schist may contain typical metamorphic minerals such as garnet, staurolite, or kyanite. In these cases, the index mineral is used as an adjective in the rock name (e.g., garnet schist or garnetifierous schist).

>> If derived from basalt, green or black amphibole is the common mineral and may be termed a greenschist or amphibolite.

> Arizona examples - Pinal Schist (central and southern Arizona), Vishnu and Brahma Schists (Grand Canyon).

> A foliated, coarsely crystalline, distinctly banded metamorphic rock.

> Easily recognizable by its well-developed alternating layers (gneissic banding) of light and dark minerals.

> The light-colored minerals typically include quartz and feldspar, while the dark minerals are generally biotite and/or amphibole.

> Metamorphic grade - High / high temperatures and directed pressures (regional metamorphism).

> Protoliths - Different varieties of gneiss form from many protoliths (mudstone, various volcanic and plutonic igneous rocks). Typically termed "granitic gneiss" if derived from granitic rocks.

> Arizona examples - Catalina Gneiss (in Sabino Canyon near Tucson), Estrella Gneiss (western part of South Mountain in Phoenix), Brahma Gneiss (Grand Canyon).

Nonfoliated Rocks

> A non-foliated, crystalline metamorphic rock.

> Composed mostly of recrystallized calcite or dolomite (carbonate minerals).

> Recrystallized calcite/dolomite crystals are relatively soft (H=3) and can react with HCl acid.

> Metamorphic grade - Low to high / moderate to high temperatures and low to high directed pressures (contact / regional metamorphism).

> Protoliths - Derived from carbonate rock (limestone or dolostone).

> Arizona examples - Bass Limestone (Grand Canyon) - it's really more of a marble.

> A non-foliated, crystalline metamorphic rock.

> Made mostly of recrystallized quartz.

> In many quartzites, the sedimentary features (bedding, cross beds or ripple marks) from the sandstone are still preserved.

> Recrystallized silica grains create a very hard rock that does not react with HCl acid.

> Metamorphic grade - Low to high temperatures and low to high directed pressures (contact / regional metamorphism).

> Protoliths - Derived primarily from sandstone under conditions of high temperature and low-to-high directed pressure (contact / regional metamorphism).

> Arizona examples - Mazatzal Quartzite (central Arizona), Dripping Springs Quartzite (central Arizona), Bolsa Quartzite (southeastern Arizona).

Other Metamorphic Rock Types

There are many other varieties of metamorphic rocks. A few important examples that we may use in this class are described below.

Metabasalt![]() / Greenstone

/ Greenstone![]() / Amphibolite

/ Amphibolite![]()

> Variably metamorphosed mafic volcanic rock that may or may not be foliated.

> Original phenocrysts and volcanic structures may be preserved, unless obliterated by metamorphism.

> Minerals include chlorite, epidote, amphibole, etc.

> Metabasalt is a generic term used for lower grade rocks with recognizable basaltic protoliths.

> Greenstone has abundant chlorite (green color) and forms from low to moderate grade metamorphism (greenschist facies).

> Amphibolite has abundant amphibole and typically forms from intermediate to high grade metamorphism (amphibolite facies).

> Metamorphic grade - Low to high / low to high temperatures and directed pressures.

> Protoliths - Mafic volcanic rocks.

> Arizona examples: North Mountain Greenstone (Phoenix), Iron King Volcanics (Bradshaw Mountains).

> Variably metamorphosed intermediate and felsic volcanic rocks that may or may not be foliated.

> Original phenocrysts (typically feldspar and quartz) and volcanic structures may be preserved, unless obliterated by metamorphism.

> Minerals include chlorite, epidote, micas, amphibole, feldspar, quartz, etc.

> Metaandesite is a generic term used for lower grade rocks with a recognizable andesitic protolith.

> Metarhyolite is a generic term used for lower grade rocks with recognizable rhyolite protolith.

> Metamorphic grade - Low to high / low to high temperatures and directed pressures.

> Protoliths - Intermediate to felsic volcanic rocks.

> Arizona examples - Spud Mountain Volcanics (central Arizona), Iron King Volcanics (central Arizona), Red Rock Rhyolite (central Arizona), Rama Schist and Gneiss (Grand Canyon).

Metaconglomerate![]() & Metabreccia

& Metabreccia

> Metaconglomerate and metabreccia are variably metamorphosed conglomerates and breccias that may or may not be foliated.

> The cement between the clasts is recrystallized, so the rock breaks across the clasts (instead of around the clasts in a sedimentary conglomerate).

> If foliated, metaconglomerate can have elongated clasts and is termed a stretched-pebble conglomerate.

> Metamorphic grade - Low to moderate / low to moderate and high directed pressure (regional metamorphism).

> Protoliths - Derived from conglomerate, sedimentarybreccia, and volcanic breccia.

> Arizona examples - Barnes Conglomerate (central Arizona), Cottonwood Cliffs (northwestern Arizona), many other local occurrences in Proterozoic units.

> A foliated, distinctly banded high-grade metamorphic rock.

> Distinctively banded into igneous and metamorphic layers. Contorted folds and veins are commonly abundant.

> May include garnet, sillimanite, etc.

> Formed under extreme temperature and pressure conditions (regional metamorphism and partial melting) and represents the highest degree of metamorphism.

> Metamorphic grade - Ultra-high / very high temperatures and directed pressures (regional + contact metamorphism).

> Protoliths - Any.

> Arizona examples - Within the Brahma Gneiss (Grand Canyon).

> A foliated, fine-grained metamorphic rock.

> Derived from the recrystallization and ductile flow along a shear zone during deformation.

> Metamorphic grade - High / high to very high temperatures and directed pressures localized along fault planes and shear zones (cataclastic and shear zone metamorphism).

> Protoliths - Any.

> Arizona examples - Many localized examples, including in the Shylock shear zone (central Arizona), at South Mountain (in Phoenix), etc.

Identifying & Interpreting Metamorphic Rocks

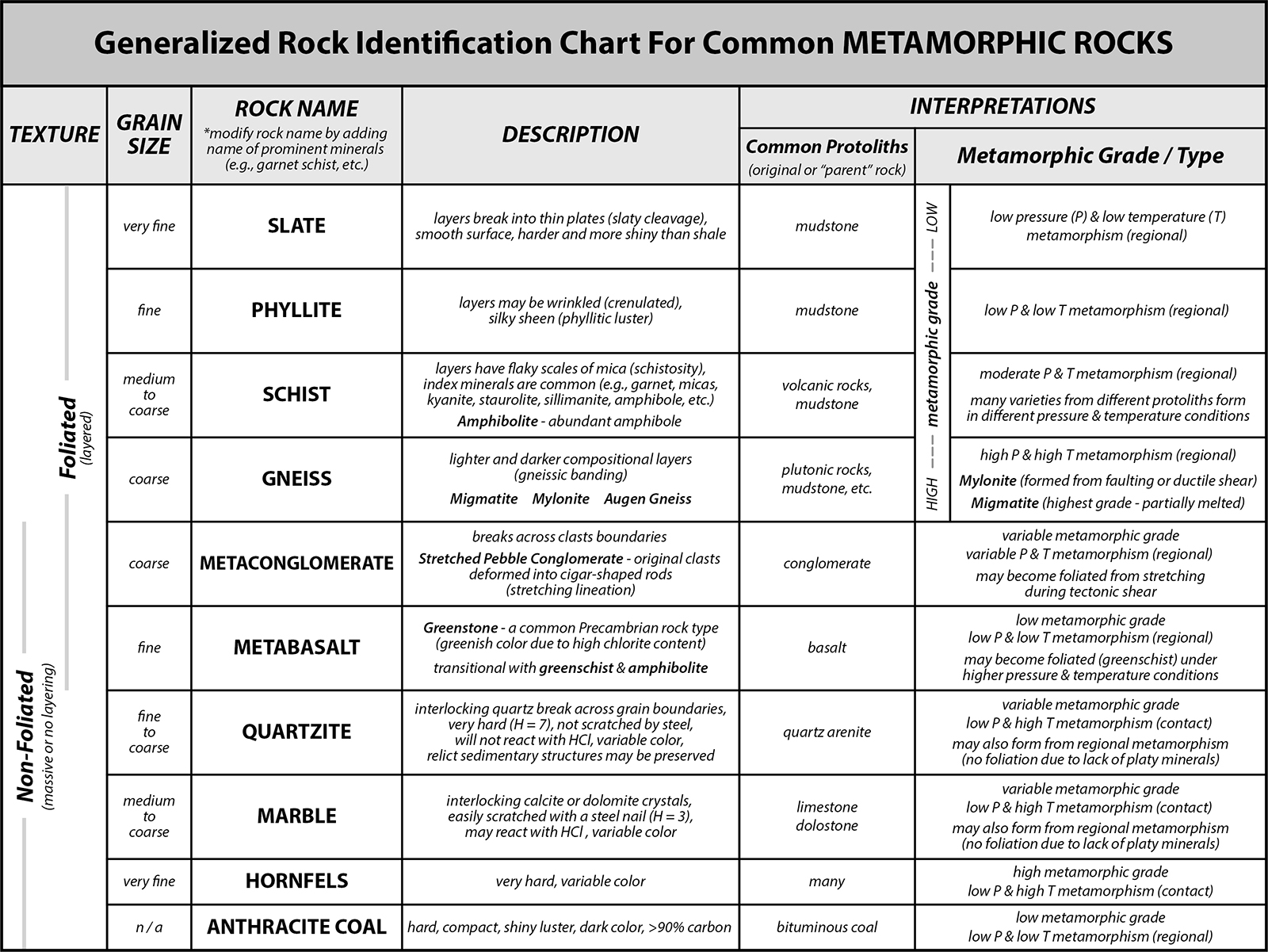

Metamorphic rocks can be easy to recognize and identify because there are only two major textural types and the rocks are fairly distinctive. On the other hand, metamorphic rocks can be some of the most challenging to identify and interpret.As with igneous and sedimentary rocks, observing the arrangement of minerals (texture) is critical in identifying metamorphic rocks. To identify and interpret metamorphic rocks, refer to Figure 7-4 and follow these steps:

Identify the Rock

Determine whether the rock texture is foliated or non-foliated. Also identify any specific metamorphic textures (slaty cleavage, schistosity, etc.).

If the rock is foliated

> If foliated, determine the specific type (slaty cleavage, phyllitic cleavage, schistosity, gneissic banding).

> Choose the rock name from the Metamorphic Rock Identification Chart in Figure 7-4.

If the rock is non-foliated

> If non-foliated, determine mineral composition. Test to see if the rock reacts with HCl acid (it will react if made of calcite), or scratch the rock to check its hardness (quartz is hard, H=7; calcite is soft, H=3).

> Choose the rock name from the Metamorphic Rock Identification Chart in Figure 7-4.

Interpret the Protolith & Conditions of Metamorphism

You can also make some simple interpretations about the original rock type (protolith) and origin of the metamorphic rock.

Protolith

> The metamorphic rock composition and any index minerals will help narrow down protolith choices, but be aware that there may be more than one possible answer.

Conditons of Metamorphism

> The type of foliation and any index minerals can help determine the nature of pressure and temperature conditions during metamorphism.

> IMPORTANT - Since non-foliated rocks generally lack platy minerals required for foliation, they may also have formed by regional metamorphism.

|

Figure 7-4. A rock identification chart for common metamorphic rocks. Click HERE for a printable PDF version. |

* IMPORTANT *

Using the PDF link above, print a hard-copy version of this chart for use in this lab and the lab quiz.

For the questions A01 through A10, refer to the Metamorphic Rock Identification Chart (Figure 7-4).

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()