The definition of average acceleration is:

![]()

According to this definition, the vector average

acceleration is obtained by dividing a vector by a scalar. Since the scalar (![]() ) is always positive,

this definition indicates that the two vectors (

) is always positive,

this definition indicates that the two vectors (![]() and

and ![]() ) have the same

direction. We would like to apply this definition to find the direction of the

acceleration at point D which is a turning

point. Then

) have the same

direction. We would like to apply this definition to find the direction of the

acceleration at point D which is a turning

point. Then ![]() and

and ![]() in the definition

correspond to an interval that spans point D,

i.e., an interval with an initial point just before point D and with a final point just after point D. The diagrams below illustrate this idea

graphically.

in the definition

correspond to an interval that spans point D,

i.e., an interval with an initial point just before point D and with a final point just after point D. The diagrams below illustrate this idea

graphically.

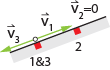

Suppose

that a ball rolls uphill along a straight track from point 1 to 2. Point 2 is

a turning point. Afterward, the ball rolls back downhill from point 2 to 3.

Points 1 and 3 are the same point. As the ball rolls uphill, it slows down.

As it rolls downhill, it speeds up. .

Suppose

that a ball rolls uphill along a straight track from point 1 to 2. Point 2 is

a turning point. Afterward, the ball rolls back downhill from point 2 to 3.

Points 1 and 3 are the same point. As the ball rolls uphill, it slows down.

As it rolls downhill, it speeds up. .

Recall that the change in velocity between the final point (point 3) and the initial point (point 1) is:

![]() .

.

This is equivalent to saying that ![]() is the quantity that

must be added to the initial velocity in order to obtain the final velocity:

is the quantity that

must be added to the initial velocity in order to obtain the final velocity:

![]()

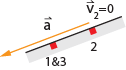

The

diagram at right shows the vector (the red vector) that must be graphically

added to vector

The

diagram at right shows the vector (the red vector) that must be graphically

added to vector ![]() to obtain

to obtain ![]() . Hence, the red vector

must be

. Hence, the red vector

must be ![]() .

.

According to the definition of average acceleration,

![]()

Since ![]() is a positive scalar,

the direction of the acceleration must be the same as the direction of the

change in velocity. The relative magnitudes of the

is a positive scalar,

the direction of the acceleration must be the same as the direction of the

change in velocity. The relative magnitudes of the ![]() and

and ![]() depends on the value

of

depends on the value

of ![]() .

.

If the

interval is short enough, then the average acceleration for the interval is

equal to the instantaneous acceleration at the midpoint of the interval, point

2. This is illustrated in the diagram at right. Notice that the acceleration

points down the incline.

If the

interval is short enough, then the average acceleration for the interval is

equal to the instantaneous acceleration at the midpoint of the interval, point

2. This is illustrated in the diagram at right. Notice that the acceleration

points down the incline.

In summary, the acceleration at a turning point is not zero. It points down the incline.