Part C

Geologic Map Basics

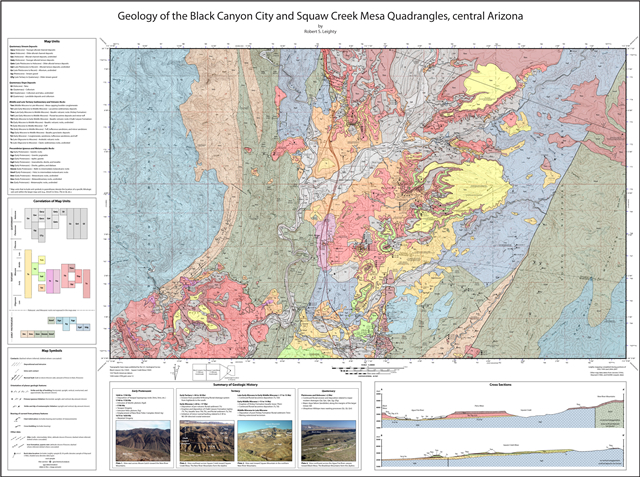

Geologic maps show the distribution of different rock units and structures (like faults and folds) at the surface. These maps are the fundamental medium by which a geologist describes and interprets the geology and geologic history of an area. I like to view geologic maps as unique earth science portraits drawn by a scientist-artist. Traditionally, a geologic map is created by a field geologist who hikes across an area and describes the composition and distribution of various rock types encountered. A geologic map begins to take shape as different map units are drawn and labeled on a topographic base map. Figure 2-17 shows a geologic map for an area north of Phoenix, Arizona. This activity is very time-consuming and may take days, weeks, months, or years, depending on the size of the area, complexity of the geology, the difficulty of the terrain, etc. Data can also be collected remotely, like from an orbiting satellite or automated rover. This is how we have mapped the geology of most of the Moon and several other planetary bodies.

|

|

|

|

Figure 2-19. James studies the Grand Canyon geologic map in the class room (left). Chris presents his own geologic map at a Geological Society of America annual meeting (right). |

|

Map Content

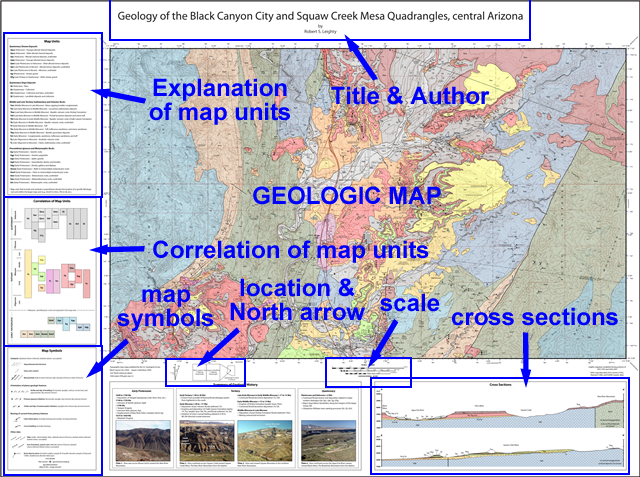

There are many types of geologic maps, and the layout and content can vary widely. These maps may be in color or black & white, small or large in size, very simple or highly detailed, hand-drawn or digital, etc. Most maps will include some or all of the components highlighted in Figure 2-20.

|

|

|

Figure 2-20. Typical content of a geologic map. |

Let's review a few of the more important items, using the map in Figure 2-20 as an example:

Title & author(s) - Maps should be titled, with the authors listed. For this map, the sole author is Robert S. Leighty.

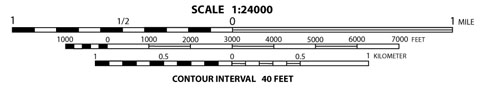

Map scales - As with topographic maps, graphical and ratio scales are typically included so the reader can understand distances and areas represented on a geologic map.

Topographic base map - Geologic maps are commonly constructed on a topographic base map, but not always. If present, the topographic contours are typically printed lighter than the geologic lines. The Black Canyon City and Squaw Creek Mesa quadrangles serve as the topographic base for this map. When topo base maps are included in the map, a contour interval may also be listed (in this case, it's 40 feet). Geographic location of the map area may also be included.

North arrow - Geologic maps should include a north arrow to show geographic north. Some will show the difference between geographic north and magnetic north (a.k.a. the magnetic declination).

Spatial coordinate markings or grids - Many maps will include coordinate information (latitude/longitude, UTM, etc.) allowing determination of precise locations on the map.

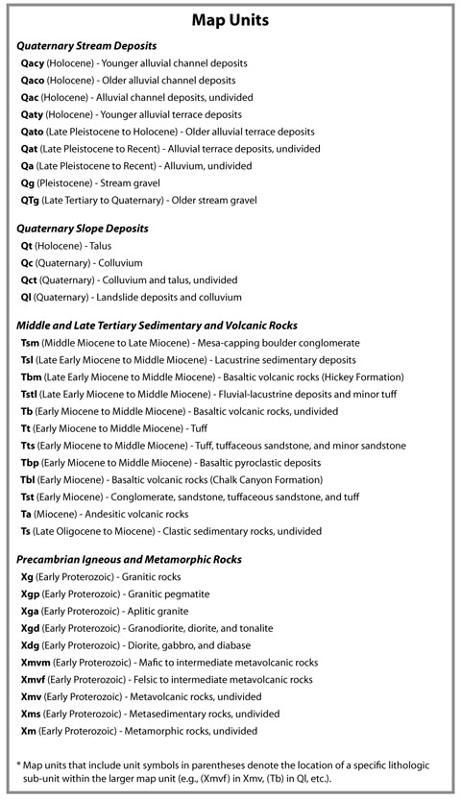

Map Units - The core data of any geologic map lies in the distribution of map units, each having distinctive physical characteristics. A fundamental map unit is a Formation, which is a rock unit (like the Texas Gulch Formation) that can be distinguished from other units in the field. It must be mappable, meaning that it must cover a large enough area to be shown on a geologic map. A lesser unit is called a Member, and several members combined can make a formation. Alternatively, several similar formations can be joined together into a larger Group (like the Big Bug Group), and groups can likewise be joined into a Supergroup (like the Yavapai Supergroup). Rock formations are typically named after the location (type locality) where the rock unit was first described or is best represented, but can also refer to the composition of the rock unit or just be a name.

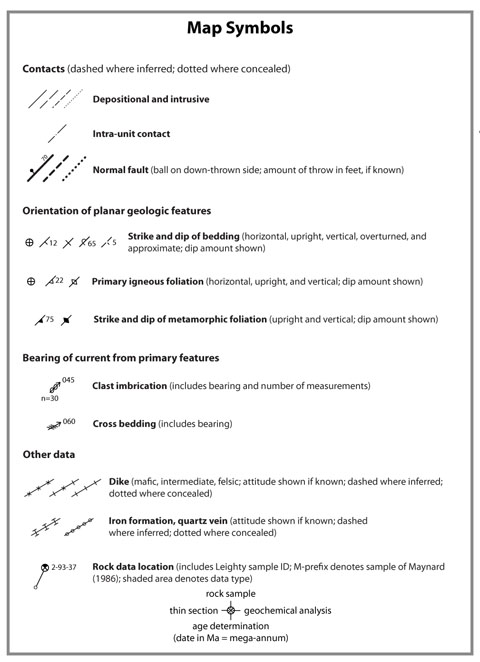

Map unit boundaries are delineated by contacts. Solid line contacts mean that the location of the map unit boundary is relatively sharp or well-located, whereas a dashed contact may imply a gradational or less well-located boundary. Dotted contacts represent the inferred location of unit boundaries that are covered by overlying material. There are other types of contacts, depending on the type of the geologic feature present (e.g., rock units, faults, etc.). Remember, contacts are not contour lines (which are related to elevation).

Map Unit Symbols - Map units have labels or symbols that identify them. The exact symbols used on different maps can vary widely, but with most map unit symbols, the first letter is capitalized and typically represents the geologic age of the formation, whereas the second (lower case) letter is descriptive of the formation name, rock composition, etc. For example, the Hickey Formation has the map unit symbol Tbm, where "T" is the age of the formation (Tertiary period, 66-2.58 Ma), "b" is basalt (the main rock type of the formation), and "m" is middle Miocene (a more specific age description). The symbols are printed on the geologic map and in the map unit explanation.

Explanation of Map Units - All maps should have a description of the geologic map units (e.g., names, ages, symbols, etc.) so the reader knows what the different units represent. Map units are listed from oldest (at the bottom) to youngest (at the top). Brief descriptions of the map units and special map symbols are commonly present. If you see a symbol on the map that you do not recognize, then look in the explanation!

Correlation of Map Units - Maps may include a diagram showing the age relations of the various map units, with the oldest units at the bottom of the diagram. This graphic can be very helpful in understanding the age relations of the various units.

Explanation of Map Symbols - Many other symbols can be used on geologic maps and a key to their explanation is important in understanding the map. Common symbols include different types of map unit and fault contacts, rock orientation symbols (strike and dip), special geologic features (dikes, quartz veins, etc.), sample locations, etc.

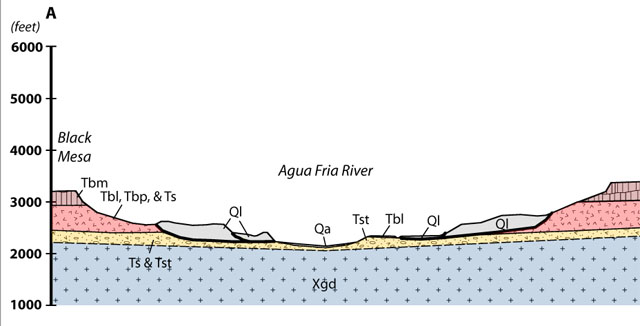

Geologic Cross Sections - Maps may include one or more geologic cross sections, which are basically topographic profiles between two or more points on the map that include an interpretation of the geology in the subsurface. The geometry of units below the surface is inferred from the orientation of rock units at the surface. Subsurface geology can also be described from canyon wall exposures, well log data, and various geophysical methods (seismic, gravity, etc.). These figures can be highly interpretive, but are very helpful in visualizing distribution of rock units below the surface. The locations of cross section lines or endpoints are marked on the map. Geologic units may be projected above the profile surface to better show the orientation of geologic structures.

Other data - Maps may include other kinds of data, like location diagrams, data tables, photo imagery, stratigraphic columns, references, etc.

|

Example 21 |

|

|

|

Look in the explanation of map units to find the name of the unit that has the symbol "Ta". |

|

Ta = Andesitic volcanic rocks |

|

Example 22 |

|

|

|

Are the location of rock data samples included on this map? |

|

Yes. Sample locations, ID, and type of data are all included. |

|

Example 23 |

|

|

|

What river is located in this cross section? |

|

Agua Fria |

|

Example 24 |

|

|

|

Is a ratio scale listed here? |

|

Yes, it is 1:24:000 |

Reading a Geologic Map

Before we move on, let's practice reading a geologic map that has many different components.

|

|

|

Figure 2-21. The Geology of the Black Canyon City and Squaw Creek Mesa Quadrangles, central Arizona. |

Answer Quiz Me! questions C31 through C40 using the Geology of the Black Canyon City and Squaw Creek Mesa Quadrangles, central Arizona geologic map (see the PDF link below).

|

Geology of the Black Canyon City and Squaw Creek Mesa Quadrangles, central Arizona |

Map Scale

![]()

Explanation of Map Units / Correlation of Map Units

![]()

![]()

![]()

Geologic Map

![]()

![]()

![]()

Cross Sections

![]()

![]()

Summary of Geologic History

![]()